'Nobody wants to live in a theme park': Will Wales finally get a new National Park?

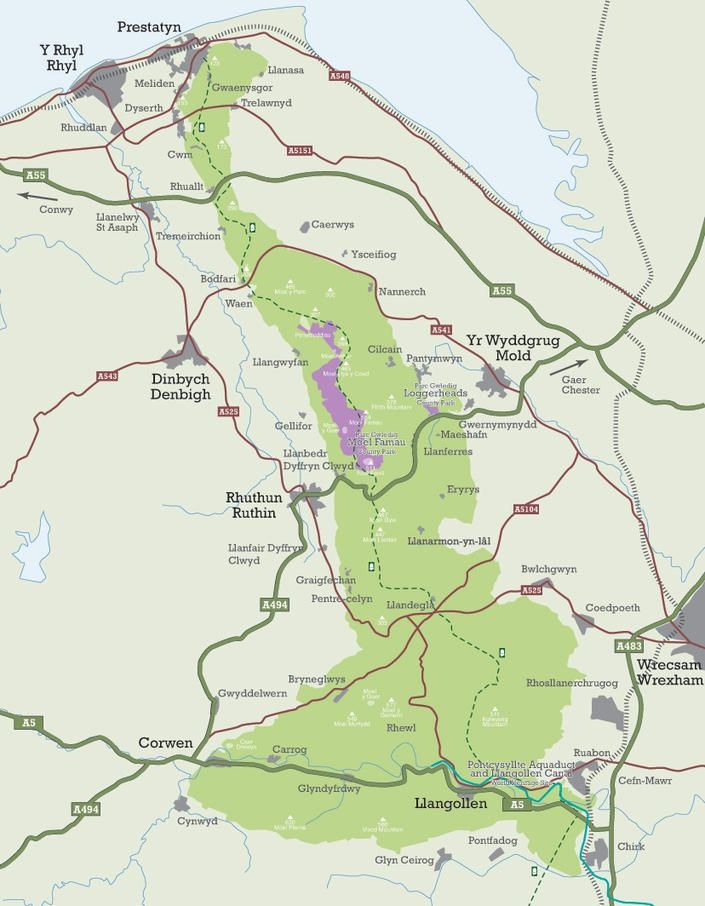

The Welsh government has pledged to turn the Clwydian Range into the country’s fourth National Park – but not everyone is happy.

Driving along the A5 through northeast Wales, you pass through a varied and complex landscape.

Blocks of coniferous and deciduous woodland are scattered across the heather moorlands and rolling hills. Iron Age hillforts perch on the summits, while the valleys are quilted with flower-rich pastures and intensively farmed grassland. This is the Clwydian Range.

Designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) in 1985 and extended to include the Dee Valley in 2011, the area is protected for both its ecological and cultural values.

Now plans are afoot to add another layer of protection. In April last year, Welsh Labour announced its intention to turn the region into Wales’ fourth National Park, joining Snowdonia, the Brecon Beacons and the Pembrokeshire Coast.

“We have so much to be proud of in Wales,” declared first minister Mark Drakeford at Labour’s manifesto launch speech. “Mae ‘na gymaint i fod yn falch amdano yn Gymru. Our landscape is among the best in the world – we just need to step outside and take a look.”

A complicated landscape

The Clwydian AONB is unquestionably a beautiful landscape. At the heart of the AONB are three moors: Ruabon, Llandegla and Llantysilio. They are all Sites of Scientific Interest (SSSI) and Special Areas of Conservation (SAC). But like much of rural Britain, their ecological states are troubled – and complicated.

Analysis of the pollen preserved in the peat of the Clwydian Hills reveals a landscape that has changed almost beyond recognition over the past 10,000 years. Before the arrival of the first farmers, the hills were blanketed in birch, pine and alder, with trees growing even at higher elevations. This forest was eventually converted to grassland by prehistoric grazing and crop cultivation, and then to the heather moorland that exists today. In other words, this has long been a working – and not a wild – landscape.

Today, Ruabon Moor is known as the “grouse capital of Wales”. It is the country’s only moorland with a full-time gamekeeper, the ecology shaped to provide an abundant population of birds for paying shooters.

This targeted management has been particularly controversial. With the involvement of the RSPB, black grouse populations have been recovering – an improvement that has been cited as evidence for the ecological benefits of driven grouse shooting. But illegal raptor persecution continues to be a thorn in the side of the industry: in 2018, two hen harriers mysteriously disappeared near Ruabon, while a raven was found to have been deliberately poisoned. The campaign group Wild Moors has called on the Welsh government to outlaw grouse shooting for good.

While farming has helped to sustain rural communities here for centuries, it comes with its own set of ecological problems. Below the purple heather uplands sweep fields of unnaturally green ryegrass, supporting an intensive grazing regime that is a world away from the more traditional practices of generations past – a shift that has come at the expense of species biodiversity in the hills.

Land of opportunity

In such a storied and complex landscape, what is the role of a National Park designation – and what, if anything, would it add to its existing designation as an AONB?

Announcing the plans for the area, Mark Drakeford promised “many benefits for agricultural communities, biodiversity and sustainable tourism.” But opinion on the ground is more divided.

The ‘look’ of the landscape is often what first springs to mind when we think of National Parks: the most rugged, dramatic and visually stunning scenery in the British Isles.

Protecting that natural beauty is enshrined in the purpose of a National Park, but so is conserving and enhancing its wildlife and ecosystems – alongside preserving its cultural heritage, and promoting the park’s “special qualities” to the public. Unfortunately, these missions do not always overlap.

These tensions have recently come to the fore in the Lake District – a landscape whose beauty is essentially agricultural, dependent on generations of farmers that have maintained an artificially treeless landscape through centuries of grazing. In England, the government's independent landscapes review concluded that the wilder elements of protected landscapes need greater protection.

Gwawr Parry, county adviser for Clwyd and Montgomeryshire at the National Farmers' Union of Wales, suggests that the presence of intensive agriculture could pose more of a conflict in the Clwydian Range than in Wales’ existing National Parks.

“You can’t really take a tractor up Snowdon,” she says. In contrast, the Clwydian Range has numerous fertile valleys hosting intensive dairy and beef production. “The biggest issue in the Clwydian Range, from what I can see, is that there’s a lot more improved grassland. I don’t know how that fits into a National Park.”

The designation process is now being conducted by National Resources Wales, the government’s environment body. Keith Davies, who is leading the review, says that nature and culture are more interrelated today than ever before.

“Our understanding of natural beauty isn’t simply the scenic and aesthetic aspects,” he says. “It pulls in biodiversity and wildlife, cultural heritage and so on. So the evidence would be gathered across the range of issues.”

For Howard Sutcliffe, the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley AONB officer at Denbighshire County Council, it is largely a question of cash. AONBs are controlled by the local authority, which means that the landscape must compete with other services, such as education and highways, for funding. National Parks, meanwhile, have a special authority of their own. “You can only be as good as your resources,” he says.

However, questions remain over where the additional funding for a fourth National Park would come from: whether there would be more money pouring into the landscape overall, or whether it would dilute the resources for ecological restoration elsewhere.

Davies says that ultimately this is an issue for the Welsh government to consider, but that he “cannot envisage additional resources not being made available” to set up and deliver the National Park Authority, and also to ensure the authority is able to positively manage the area.

Others have an eye to the economic gains that a National Park designation could bring to the people that live there. Ken Skates, a Labour MS for Clwyd South, believes it could help farmers to diversify their businesses and move towards more sustainable practices.

“I think it's fantastic that more people want to get out into the natural environment and are showing an interest in biodiversity,” he says. “Yes, National Park status could see a significant increase in the number of visitors to the Clwydian Range and Dee Valley. But with that comes opportunity.”

Local concern

If designating the Clwydian Range as a National Park was going to be easy, however, it would have been done long ago.

In 2010, the Conservative MS Darren Millar campaigned unsuccessfully for the Clwydian Range to be given National Park status – but he was accused of being “out of touch” with local communities by Plaid Cymru politician Mabon ap Gwynfor (who has since been elected to the Senedd).

“Rural communities covered by the Clwydian Range don't want a National Park and for good reason,” said Gwynfor at the time. “Not only will it severely limit their ability to develop their businesses, but it would be run by representatives who have no interest or concern in the area, taking responsibility out of the hands of the communities that live within the area.”

More than a decade later, emotions around the use and occupation of the Welsh landscape still run high, with rewilding and carbon offsetting schemes often perceived as threats to the rural way of life and to the Welsh language and culture. A 2011 survey found that, in the west part of the Clwydian AONB, almost 40% of people use the Welsh language, compared to a national average of 21% (a figure that has since risen to 29%). Though the creation of a new National Park is decidedly not rewilding, these sensitivities remain acute.

While some see economic opportunities in the potential designation, others see only threats to a way of life that has been playing out in these hills for countless generations. “For me personally, I’d not want it,” said one local sheep farmer and business owner, who wished to remain anonymous.

Living and farming in an AONB is already restrictive, and he worries that a National Park could create an added layer of bureaucracy, while also ramping up demand for houses, driving up property prices in the process. He fears that the plans could change the character of the area for the worse: “Nobody wants to live in a theme park.”

While the NFU does not yet have an official position on the designation, Parry also anticipates that it could result in changes to the farmed landscape, as pressure mounts to restore a more traditional and wildlife-friendly approach to grazing.

“I think that is why the farming community would be wary of the National Park label, because it has a perception of being a more expensive system, where you move back to the native breeds that can perhaps manage the landscape better than the continental types that have been brought in,” she says.

Even so, Parry is keen not to focus on the negatives, and says she will be asking the government about opportunities that National Park status might bring to the Clwydian Range. “If it means that there are more businesses interested in establishing themselves in the area, then that provides more job opportunities, which means in turn that there are more young people staying,” she says.

In particular, she is keen to see an investment in resources that would help interpret the agricultural landscape for the general public. “It would be an opportunity to reach out to more of the Welsh population in terms of how important agriculture is here.”

Last year, the minister for climate change, Julie James, attempted to reassure locals that the National Park designation would not be to their detriment, and that the government was bringing in measures to increase the stock of social housing and tackle the growing number of second homes.

Farmers, business owners and residents will all have a chance to air their concerns as the government begins its lengthy consultation process. Their views, says NRW’s Keith Davies, will help form “the final decision on the status of the area” – although it will probably be around four years before the outcome is decided.

Nonetheless, with Wales having declared a climate and nature emergency, the restoration of landscapes is higher up the agenda than ever.

The National Parks of Britain are much loved by the public, but the degraded state of their land has led to growing discontent. The debate over the Clwydian Range will test the balance between manmade beauty and thriving wild space – and, ultimately, whether the communities that live there can find a place for both in their hearts.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.