Stories in the peat

Through the earth's natural archives, Annie Worsley explores the history of her Highlands home.

I live in a small valley in Northwest Scotland, surrounded on three sides by mountain ranges and to the west by sea and islands.

As well as the single-track tarmac road connecting our crofting township with others along the coast, there are several old trails leading out of the valley. One track rises gently up the valley sides and follows an ancient route inland once used to herd cattle from South Erradale towards the old drover roads out of Gairloch.

As it rises, the path weaves through large expanses of peat and alongside hidden lochs. Peat bogs are formed from plant material, especially specialist species such as sphagnum mosses. They are topped by a multi-coloured living carpet of moss, threaded by the fibrous roots of herbs, heathers, bog myrtle, sedges and grasses.

Peat is a good storyteller. It preserves atmospheric fallout – pollen and spores, dust, volcanic ash, pollutants – and the larger remains of insects, plants (including tree roots, trunks and branches) and animals once living on or near the peatland.

Each year new material is added to the bog’s surface. Information about global atmospheric change, and regional landscape-scale as well as site-specific history, becomes entrained within the growing bog.

It takes thousands of years for peat to accumulate. In Scotland, a centimetre every ten years or more would be regarded as swift. Cutting down through peat takes us back through time, a metre for every ten centuries. An exposed edge may reveal glimpses of the past, old books left open for us to read, with pages on climate and changing landscapes. The way to read these pages is by microscopy.

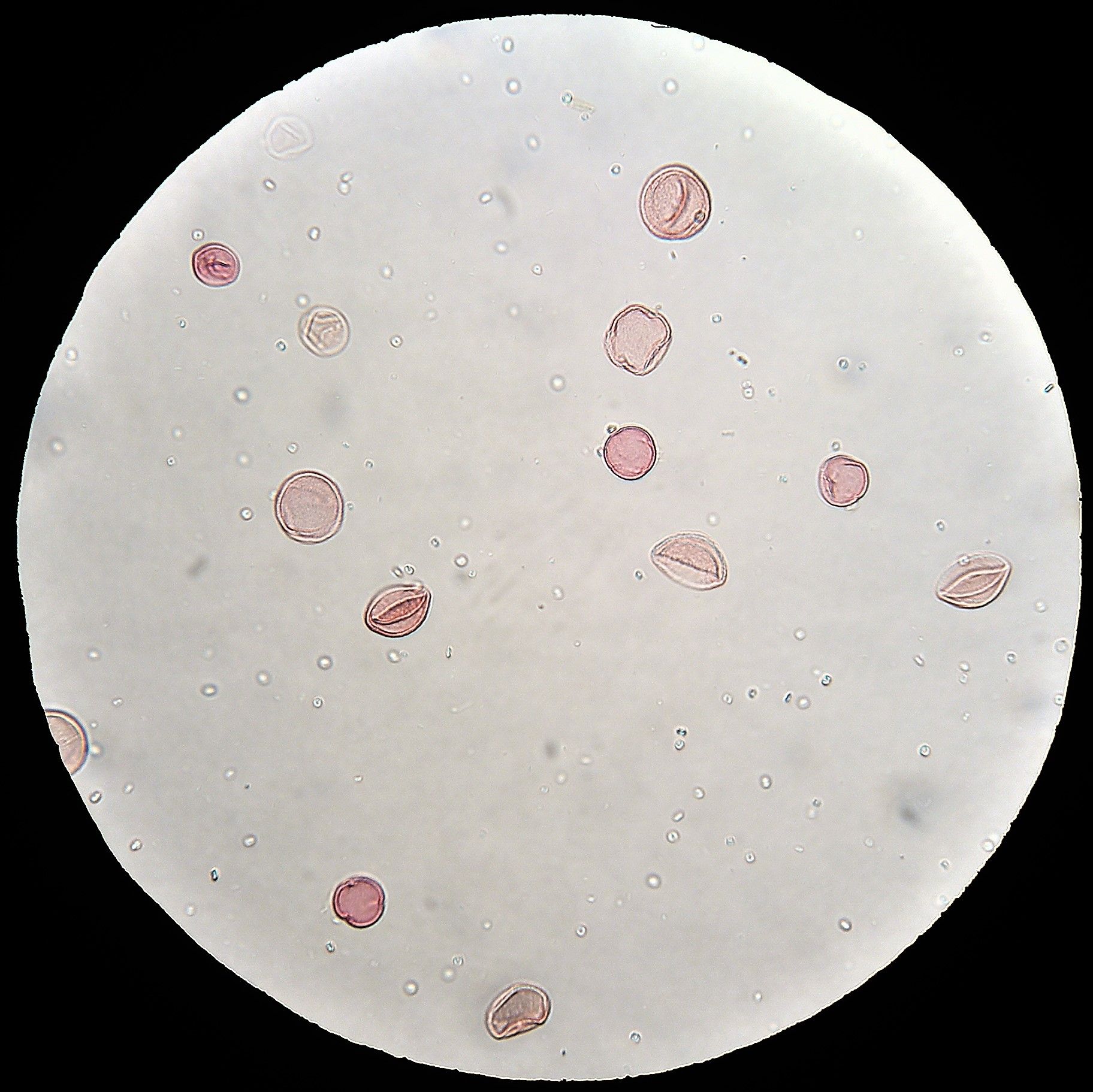

A single pollen grain or cell has a species-specific character. Its physical dimensions – shape and size – together with the patterning of its outer walls, are unique. There may be openings of different kinds – some circular, others boat shaped – which vary in number and location. The surface of a grain may be sculpted in a particular way: smooth, stippled, striped, lacy or like crazy paving. There may be air sacs or tiny protuberances such as spines, filaments or nodules.

It is possible to identify many grains to species level. Oak pollen is very different to pine or birch; grass grains are very different to sorrel or heather.

By identifying and counting the number of different species in any given sample of peat, it is possible to go back in time and reveal information about the type of vegetation community in existence in the area, one hundred, one thousand or ten thousand years ago.

And, perhaps even more remarkably, it may be possible to deduce how people were affecting the plant communities through forest clearance or agricultural activity.

We know the landscape here was once wooded. Oak, pine, hazel and birch covered much of the Highlands. But other species tell of forests with small clearings, openings to the light. Hazel, once used by palynologists as an easily identifiable marker to help size other pollen grains, is now known to be indicative of more open forested landscapes. In order to flower and produce nuts, hazel needs an open canopy, not the dense dark closed woodlands once thought to cover Britain.

Thus, peat is a natural library of landscape, recorded not in pen and ink but in the microscopic fragments and colourful fabric of its being. Some peat is carbon-black, some cow-dung brown. The darker the colour, the warmer the climate at the time of formation.

In hot, dry summers bogs (and plants) dry out, bacterial action intensifies, the process of decay speeds up so the form and structure of bog plant species are destroyed. This ‘humification’ produces the darkest peat. In colder, wetter summers, decay slows, the peat is pale and distinct plant structures can be seen.

At the edges of fresh peat cuttings, it is possible to see variations in colour with bands of dark and pale peat indicating differences in climate – the warm Medieval period, the cold wet Dark Ages, the Little Ice Age – or even further back into prehistory.

As well as a beautiful wander among extraordinary plants, walking onto hill peats or valley bogs can therefore become a journey into the past, both onto and through songs and stories of peoples long gone.

One summer on the drover’s road, I walked thigh-high in vegetation. Every stride was accompanied by the alto-hum of insect wings beneath soprano birdsong. Hundreds of tiny moths, lacewings and craneflies settled on my arms, head, face and body. I felt drenched in life, cloaked by the sheer abundance, and almost completely absorbed by the living biosphere, slowly breathing in birdsong, larks, curlews and all. The peat bogs were lush and literally bouncing with energy.

This year, the ‘Great Drying’ of May and the hottest June on record will leave its mark. For the first time in all my years of peat-bog wanderings, my boots have remained completely dry, even when crossing the largest and normally wettest tracts.

Bog surfaces were crisped and crunching underfoot. Sphagnum mounds were bleached of colour and shrunken, and so dry they resembled scrunched up parcel paper. Any exposed peat was deeply cracked and hard.

On a recent walk I paused to watch birds skimming back and forth over the vegetation. The great blankets of bog shimmered and glittered in the heat and the lochs dazzled as they reflected the forget-me-not blue sky. It was beautiful yet troubling. I found it hard not to think about fire, the release of carbon into the atmosphere, the loss of species.

July has brought heavy showers. As I type, the ground is soaking up the water; the land is greening quickly. Pollen and spores will eventually fall to the surfaces of bog and loch and become assimilated within the accumulating layers as part of the growing archive of life.

I am concerned about a future in which peatlands dry out and do not recover, although it will still be possible to ‘read’ the fossil peats and loch sediments.

Perhaps in years to come someone will see this point in time as a marker horizon, as confirmation of a warming world and changing ecologies. They may find evidence of our work here in this valley and perhaps some of our secrets will be revealed.

Annie Worsley's new book, Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands, will be published on 3 August by William Collins.

This article was made possible by funding from The Pebble Trust.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.