The media has failed with its reporting on meat

Newspapers are not holding the meat industry accountable for its role in the climate crisis.

Newspapers are failing in their coverage of animal agriculture.

‘Failure’ is a subjective term, of course – it depends on the objective. But if the objective is to reflect the contribution of meat-eating to global emissions, and to hold powerful business interests accountable, then the media has certainly failed, according to a new study by academics from Oxford, Stanford and the State University of New York.

The researchers chose four newspapers from the UK and the US, representing both sides of the political spectrum. On the right, they picked the Telegraph and the Wall Street Journal, and, on the left, they picked the Guardian and the New York Times. Each of these papers cover climate change regularly, although the left-leaning ones have more dedicated environmental reporters.

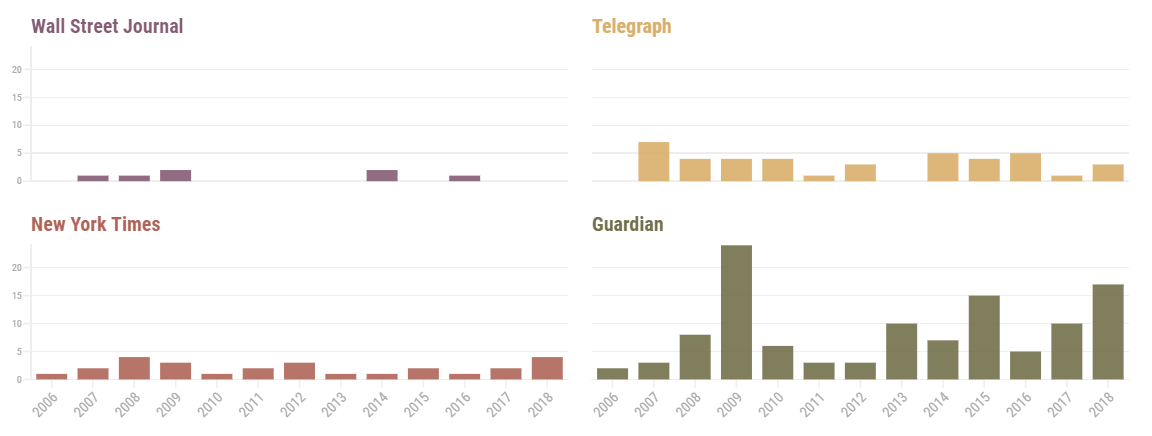

They used a set of keywords to identify all articles that mentioned both climate change and animal agriculture between 2006 and 2018. This created a sample of 5,515 articles. The researchers whittled the sample down to those exploring the subject in depth, leaving just 188 articles.

I’ve made the following graph to show how these were distributed across the four newspapers.

So what do these articles show about the media’s coverage of meat-eating in the context of climate change?

Firstly, that the volume of coverage is bafflingly small. Over the 12-year time period, the four newspapers published nearly 114,000 articles that referenced either ‘climate change’ or ‘global warming’. Only four percent of these even mentioned animal agriculture. That’s way out of proportion to the emissions that the sector produces.

Within the context of their home countries, the left-leaning newspapers both published more on agriculture and climate change than their right-leaning counterparts (although it should be noted that the Telegraph still published more than the New York Times). The issue was covered more regularly in the UK than in the US.

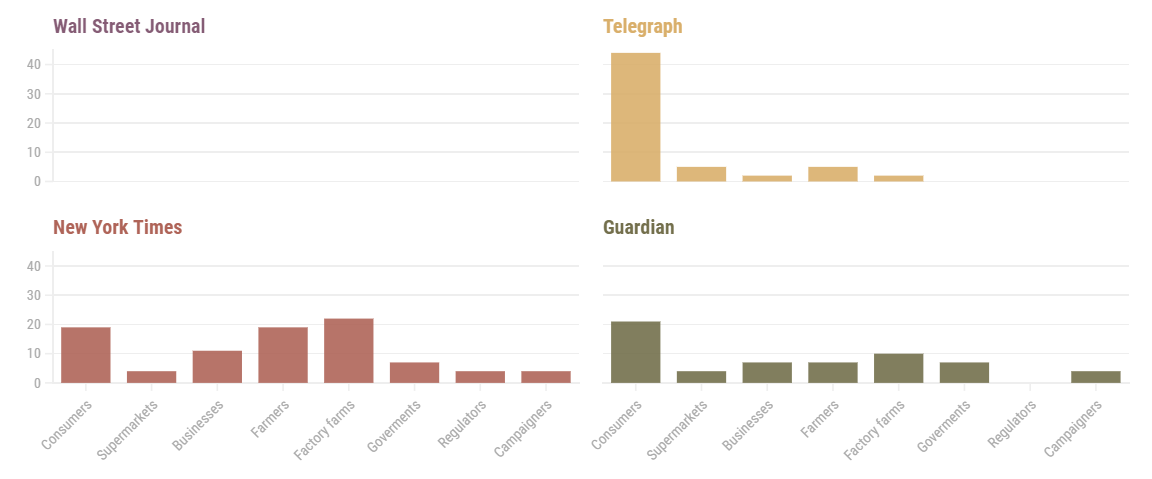

The study also examined the nature of the coverage, including who bore the brunt of the blame for agricultural emissions. The researchers found that responsibility tended to be spread between eight actors: consumers, supermarkets, businesses, farmers, factory farms, governments, regulators, and campaign groups.

Consumers were overwhelmingly the group most held responsible; they were mentioned in 47 of the 188 articles – more than businesses and factory farms combined. In other words, the problem of agricultural emissions is largely presented as the fault of individual meat-eaters, rather than those who produce, sell and regulate meat products.

The following graph shows the percentage of articles across from the sample that mention any one of these actors. (Weirdly, the Wall Street Journal did not mention any responsible actors at all.)

Many campaigners argue that this journalistic focus upon consumers is letting large food companies off the hook. Compared to Shell and BP, meat producers like JBS, Tyson and Cargill fly beneath the radar of public censure – yet, according to one study, these three companies together emit more than France.

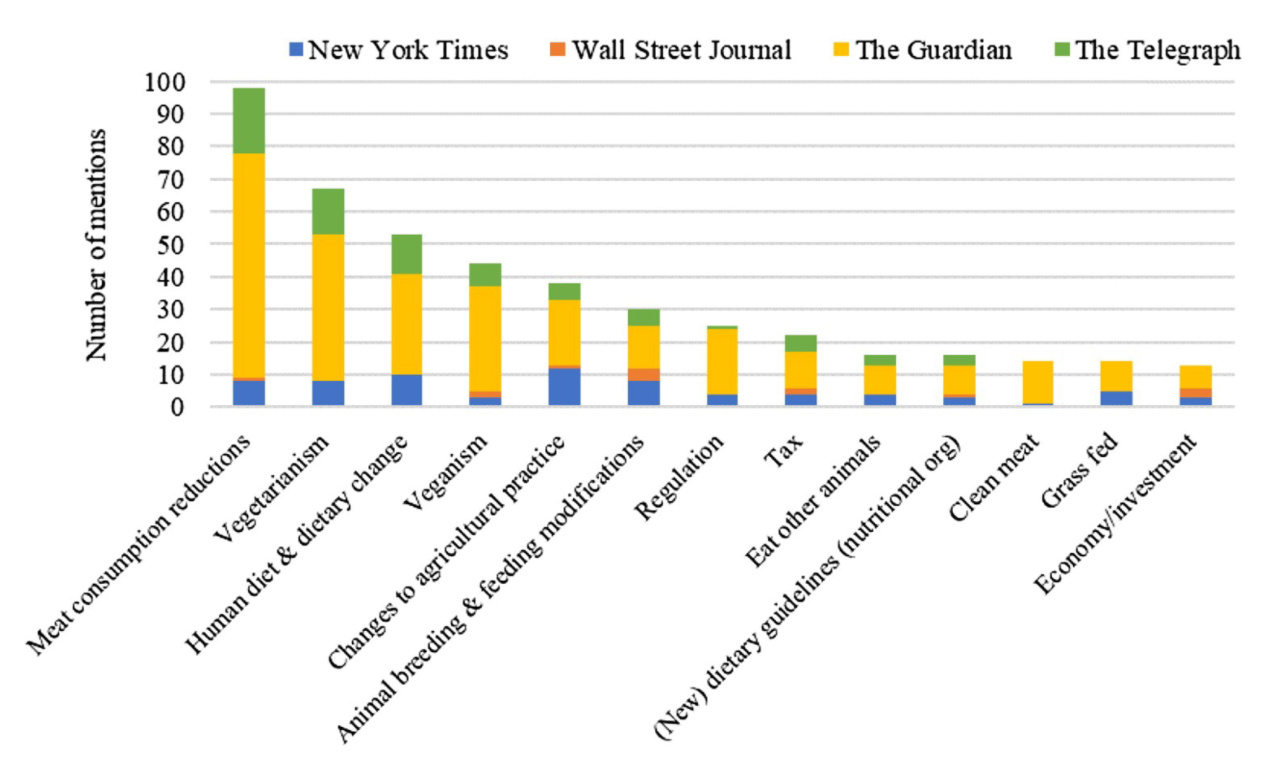

So how do journalists frame the solutions to agricultural emissions? The researchers have studied that, too.

Unsurprisingly, responsibility again falls to the individual consumer. Behavioural changes – such as reducing meat consumption, or going vegan or vegetarian – received far more attention than changes to agricultural practice, taxes and regulations, or development of alternative proteins. This is less apparent in reportage on the energy transition, where fossil fuel companies and governments shoulder much of the blame.

The graph below, taken from the paper, shows how frequently each of the various solutions were mentioned by the four newspapers.

The ultimate objective of any intervention is that people eat less meat, or meat that has been farmed in a less carbon intensive way. But if we are simply waiting for society to feel a collective pang of guilt and give up burgers, then we may be waiting quite some time.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Last year, the Committee on Climate Change released a report that included recommendations for how the government could encourage the shift towards low-carbon diets. It suggested funded training in plant-based cooking, mandatory labelling for environmental impact, and financial incentives for farmers to shift from livestock to horticulture.

How journalists choose to cover agriculture can actively damage efforts to tackle climate change. Newspapers help the public to calibrate their sense of what is important. If journalists are silent on agriculture, people will assume that it is relatively insignificant, and will also lack the knowledge to act.

Moreover, some argue that focusing on the individual “helps to take the responsibility off the necessary systemic changes that governments should be introducing and distracts attention from the holding to account of large (polluting) corporations,” the paper says.

Perhaps most importantly from a journalistic perspective, these trends do not reflect reality.

At 14.5% of the global total, meat consumption has an enormous carbon footprint. It’s on par with transportation, and that doesn’t include the carbon opportunity cost of how the land could be used instead. Of course, allocating newspaper coverage based on a sector’s share of global emissions would be a whimsical editorial strategy – but there’s good reason to argue that livestock should feature in more than four percent of climate reporting.

So why do journalists persist in writing about meat in this way? The researchers suggest two factors.

Firstly, they note that politicians and environmental NGOs have been historically reluctant to advocate policies in this area. “This may in turn be due to their belief (at least until recently) that the encouragement of dietary change is a harder ‘sell’ to the public than changes to energy sources and transport means, or from a general reluctance to take on powerful lobbying interests in the farming sector,” the authors write.

Secondly, it’s possible that journalists are subject to their own biases. Reporters eat meat, too, and may have their own views on how to tackle the climate crisis. The researchers also note that meat-eating is tied to masculinity – and that newsrooms, and particularly editorial roles, tend to be dominated by men.

“It does not seem far-fetched that one factor explaining little media attention could be human eating habits in general and the unwillingness to change those habits,” the researchers say.

One bright spot in the media landscape is the Guardian’s Animals Farmed initiative, which was launched in February 2018 and has helped to increase scrutiny of food production. But, across newsrooms more generally, it is time for journalists to take courage – perhaps confront their own biases – and tackle the meat issue head on.

Image credit: Pexels

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.