‘Storm worse than ever today’: how schoolteachers tracked weather in the Outer Hebrides

School logbooks from the nineteenth century reveal how islanders coped with a period of particularly stormy weather. In their resilience is a lesson for the future.

Big raindrops clattered on the school roof. Gusts troubled the windows. And an angry wind crept round to the door, wheezing through cracks in the woodwork. At last, the teacher relented.

Very well. You may sit by the fire.

The teacher, who worked on the island of Grimsay in the Outer Hebrides, noted this concession in a note scribbled in the school logbook, dated 4 February 1881. “Several of the younger children wretchedly clothed, sat shivering in their seats,” they wrote.

The Outer Hebrides, a chain of islands off the west coast of Scotland, could be considered among the most remote places in the British Isles. They are frequently pummelled by storms and flooding, which are expected to get worse with climate change. And yet, precisely because the Outer Hebrides are so remote and sparsely populated, there are few written records of what the weather was actually like a century ago – little detail about how bad it was, or how people coped in the face of it.

In 2014, Neil MacDonald, a professor of geography at the University of Liverpool, discovered a surprising way to find these things out. He and a colleague were in the Outer Hebrides, searching for records that might lay bare the region's climatological history. Eventually, the archivist who was helping them brought out a box of school logbooks that had been sitting in the storeroom of a library.

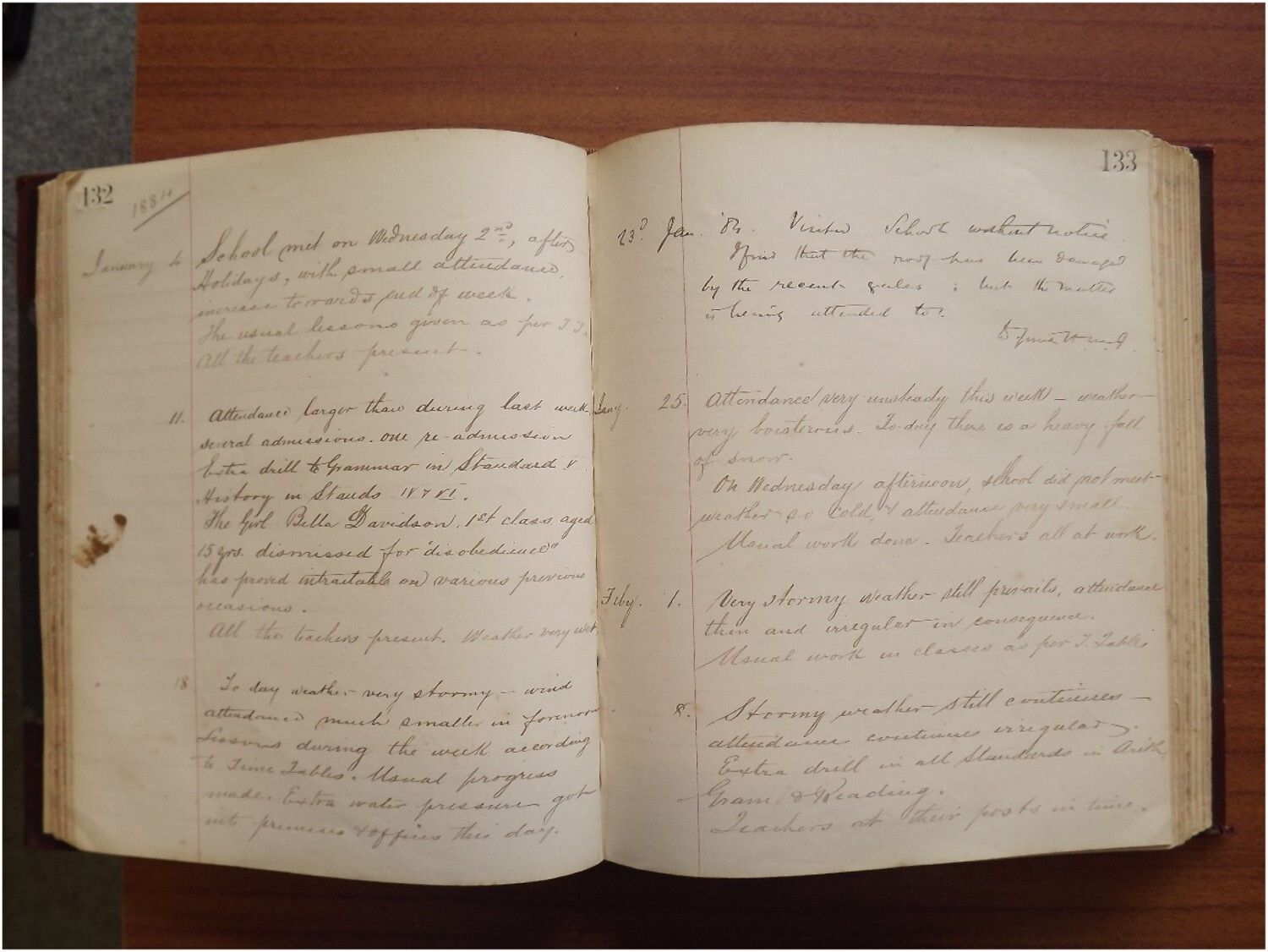

As the two academics began leafing through these volumes, their excitement swelled. Contained within was entry upon entry of records, carefully penned by schoolteachers, describing days when, for instance, the summer weather was so good that pupils were asked to help with livestock rather than go to school. Or when gales kept children at home. “Storm worse than ever today,” wrote one bedraggled teacher in 1895.

These notes weren’t written daily but they were made frequently and span many years. A picture of how the weather had behaved over a long period, and how it affected people, was emerging from the pages of the logbooks.

MacDonald looked up at the archivist and said, “Can we get some more?”

Over the ensuing months, he travelled throughout the Outer Hebrides, ultimately gathering more than 170 logbooks from dozens of schools scattered across the island chain. The dossiers covered a period from 1872 up to, in some cases, the late-twentieth century.

In a paper published last October, the researchers described how the logbooks offer a unique record of extreme weather and its impacts. Another study, published in January, argued that such accounts reveal how communities responded to climate variability.

“We just didn’t have that information from any other sources,” explains MacDonald. “To get that across so many islands and locations in a consistent format was really valuable.”

The logbooks only exist because of the Education (Scotland) Act of 1872, which made school attendance compulsory for children aged between five and 13. They were designed to allow teachers to record causes of non-attendance, hence the preponderance of weather-related comments in logs from the famously squally Outer Hebrides.

In their efforts to understand the historical climate of the islands, MacDonald and his colleagues also analysed rainfall records from a meteorological station in Stornoway on the Isle of Lewis. Such data was useful but one-dimensional. The logbooks, on the other hand, provided incidental human details that could not be gleaned from more traditional sources, including crucial information about how people actually responded to such weather.

“Very stormy day. School closed. A great many children absent for weeks on account of Influenza, sore throats, colds, skin eruptions, want of boots and clothes and the boisterous unsettled state of the weather,” wrote a teacher in 1894.

The logbooks have their own limitations. The teachers followed no systematic protocols for recording weather events, and much was likely omitted. Unsurprisingly, there are fewer entries during spring and summer, when the weather was generally better. And, although the logbooks humanise the effects of the weather, their narrow purpose means they don’t include much detail about the lives of schoolchildren and their families.

Today, the logbooks could prove unexpectedly valuable. The islanders whose stories they recorded possessed a resilience that we may all require in the coming decades.

Although they didn’t know it at the time, the teachers were documenting a particularly stormy period of Scottish history. Other reconstructions of historical weather have suggested that the 1880s and the 1940s would have been especially hard on the islanders. The peaks in snowstorms and strong winds at these times are well captured by the logbooks.

A spokesperson from the Met Office, although declining to comment on MacDonald’s findings directly, did stress the “huge value in having long historical records” that captured the variability of the Outer Hebridean weather, which “can be distinct from other parts of the UK.”

As with the UK as a whole, climate change means that the Hebrides are once again facing extreme conditions. In 2005, a huge storm with hurricane force winds struck the Outer Hebrides, killing five people, all members of the same family. They were swept away while attempting to flee in their cars. It was considered a “once in a generation” storm, says Alastair Dawson, honorary professor at the University of Dundee and author of So Foul and Fair a Day: A History of Scotland's Weather and Climate. But that might not be true for much longer. “There could be other events like this in the not too distant future,” he says.

The logbooks are not only a record of the long history of extreme weather, says MacDonald – they are also a reminder that people coped. Despite modern technology, clothing and housing, he questions whether resilience has diminished – at least in some ways – during the last century or so. If we do face even more severe storms in the decades ahead, then, arguably, we cannot count ourselves as so different from the nineteenth century Hebrideans who also battled the elements.

For Sandra Kennedy, an artist born on the Isle of Lewis and who has lived there most of her life, the accounts in the logbooks feel very familiar. “I’m obsessed with the forecast, I’ll plan my week with the forecast,” she says, describing how, today, ferries can be cut off by storms, potentially meaning a lack of supplies in local shops. Sometimes, when the wind is up, she’ll drive across the island and feel violent gusts battering the car. “It can become quite dangerous,” she adds. “Power cuts are not uncommon.”

The flippant dismissal often trotted out by climate change deniers, that reports of extreme heat waves or killer storms around the world are “just weather”, doesn’t fly in the Outer Hebrides. There’s no such thing as “just weather” for someone like Kennedy. The weather can have an underlying, even unspoken effect on people, she says. It can claim lives. “I think it’s really important to pay more attention.”

Some are forced to pay more attention than others. The logbooks reveal much about how poverty afflicted Hebrideans in the past.

Entries occasionally mention children not being able to come to school in the snow because they had no shoes. Adaptation wasn’t just about staying at home or sitting by the fire – it was about providing the children with the equipment that their parents might not have been able to afford. The records note, for example, that in South Uist efforts were made to provide better clothing, including cloaks, to children so that they did not have to sit through lessons in wet garments after walking through the rain.

Tackling poverty remains key to helping people survive climate change. Today, the Outer Hebrides have the highest rate of energy poverty in Scotland. Consider also the subsistence farmers elsewhere in the world who are increasingly troubled by drought, or the communities affected by excessive heat, especially in the tropics and the Global South – or the schools that, even today, are forced to shut due to storms or heat.

Providing water-saving equipment or planting trees to provide shade – it’s not so far from handing out cloaks to children in the Outer Hebrides in the 1800s. The logbooks could encourage a more “empathetic understanding” of climate change, suggests MacLeod Rivett, an archaeologist and author of The Outer Hebrides: A Historical Guide.

Staff at the Tasglann nan Eilean (Hebridean Archives) at Lews Castle Museum and Archives on the Isle of Lewis are now working on digitising the school logbooks, in order to make them more accessible in the future, says Seonaid McDonald, an archivist there.

Observing and understanding the weather. Feeling it. Remembering it. Knowing what to do. These are powerful tools in the face of climate change, argues Kennedy. One of her recent artworks, a series of recordings made available online last year, features people in the Outer Hebrides recalling the effects of winter storms. Oral histories, media reports, academic studies and – yes – the school logbooks all add to a heap of material that insists the weather, and our changing climate, are not things we can easily dismiss.

“It goes deeper than politics, you know,” says Kennedy. “It’s beyond that. It’s about survival, really, isn’t it?”

This feature was made possible by funding from The Pebble Trust.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.