Why does nature need the night?

An interview with Tiffany Francis-Baker, author of Dark Skies.

Why does nature need the sky to stay dark?

It’s one of the questions that Tiffany Francis-Baker explores in her book, Dark Skies. Is our preference for starry vistas simply aesthetic, or is light pollution actually impacting the natural world?

I read Tiffany’s book cover-to-cover one afternoon about a week ago, while I was feeling under the weather. Half memoir, half nature writing, her narrative delves into the world that comes to life once the sun sets – it is an account of close encounters with foxes, folkloric traditions, and moonlit journeys down river. The fact that I eventually emerged from beneath my duvet to ask my partner if we could plan a night-hike is testament to the writer’s infectious enthusiasm for the darkness.

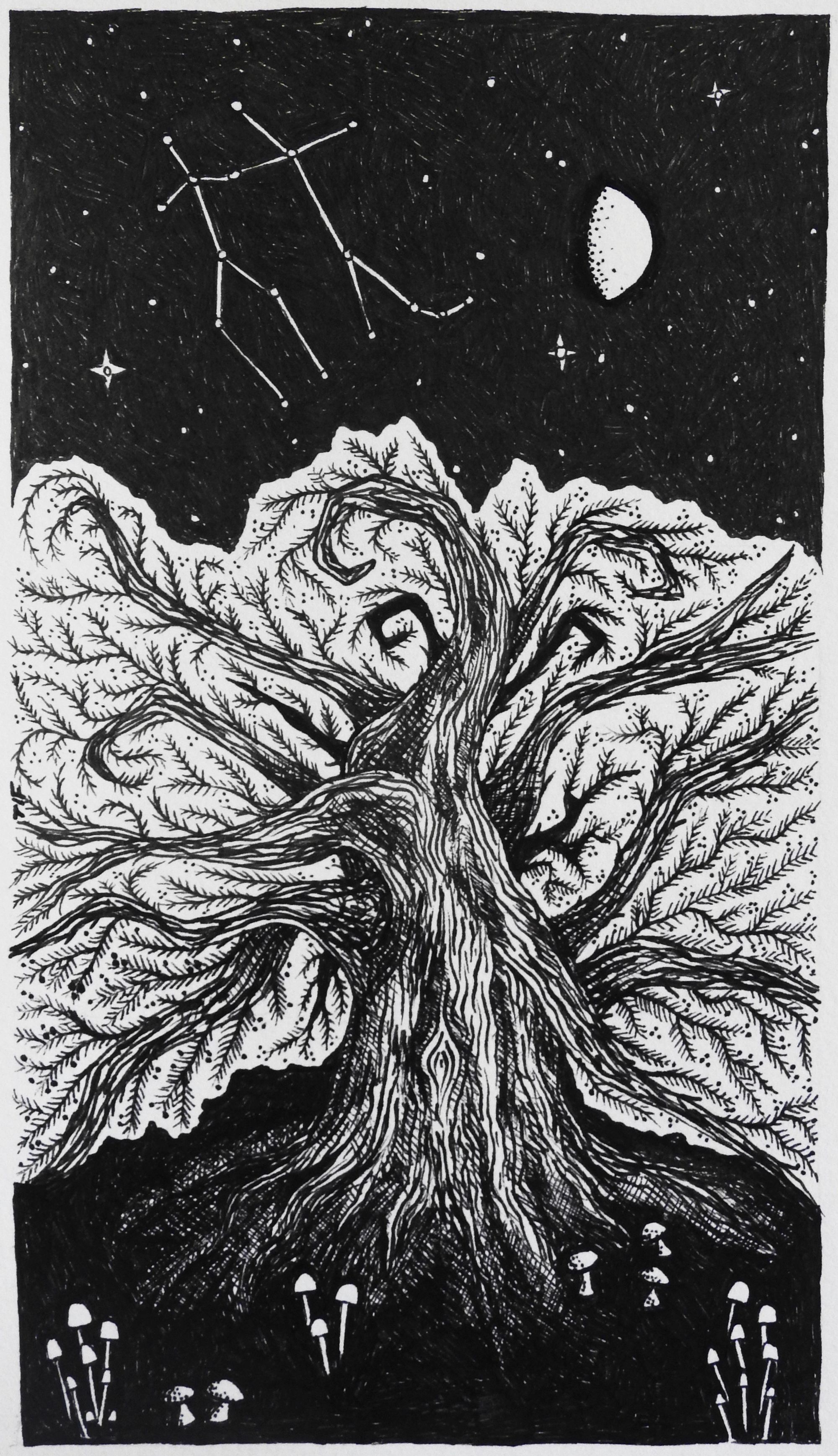

The book is also filled with wonderful illustrations (fun fact: Tiffany also designed the Inkcap logo), some of which I’ve included below. Dark Skies came out in paperback on 3 September.

Q&A with Tiffany Francis-Baker

What is it that draws you to the darkness?

I love the peace and solitude of the landscape at night. When I look up at the stars, the chaos of modern life falls away and I am able to reflect on my place within the world. Any problems or worries I have feel even less important. I think we are constantly expected to be switched on, busy and connected, and sometimes the most wonderful thing is to spend time alone in nature when everyone else is asleep.

How does your experience of nature change when you go out at night?

Being out at night means relying less on eyesight and instead tuning in to our lesser used senses. I’m used to watching birds and butterflies in the daylight, observing their behaviour based on what I can see. At night, the darkness calls on our sense of smell and touch, instead. Being more vulnerable and unsure of my surroundings feels like I’m in unknown territory – I am being watched, but I cannot see the watcher. It feels wilder and more thrilling.

How has society’s experience of darkness changed over time?

Since the discovery of electricity, we have become less synchronised with the circadian rhythms of light and dark. Before we were able to ‘control’ these rhythms with indoor lighting, we were forced to be more comfortable with it. Nowadays, few of us spend time outdoors after dark unless we’re working or on a night out, and we discourage women and children from going out at night. It has become a time for rest and retreat, avoiding the dangers, real or imaginary, that might lie beyond the front door.

Nighttime is often seen as a time of peace and quiet, while daytime is associated with activity. To what extent is this true in the natural world?

While it’s true that many species feed, travel and socialise in the daylight, one of the best times to watch wildlife is in the crepuscular hours – the precious moments around dusk and dawn. This shift between night and day provides enough cover for species to emerge from the shadows, but it is still possible for us to observe them. The dawn chorus is a great example of this – one of the most lively and raucous spectacles in nature actually begins in the dark.

How has the increasing availability of artificial light affected the patterns of nature?

In the animal kingdom, some snakes, salamanders and frogs restrict their movements when the moon is full to avoid predators being able to spot them in the moonlight. This means they tend to hunt more on moonless nights, but as artificial light pollution is spreading further across the habitats of these species, they are spending less time hunting and more time waiting for the light to dim away which, not being a natural light with natural rhythms, it never does. In cities, wild birds are also shifting the start of their early morning dawn chorus to avoid light pollution from urban developments, although researchers suspect this could also be due to noise pollution.

What can be done about light pollution?

The quickest and easiest solution is for everyone to turn off any unnecessary lighting at night, as well as using dimmers, motion sensors and timers to reduce average illumination levels and save energy. From a more technical standpoint, warm-coloured bulbs reduce glare and are proven to be less disruptive to wildlife (and human eye health), while LED bulbs also offer reduced illumination. You could also try contacting your MP to ask what they are doing to combat light pollution in your area.

Has motherhood changed your perspective of nighttime?

Absolutely! Feeding Olive around the clock means I’ve become semi-nocturnal, but I’m really enjoying the peaceful moments we share together in the middle of the night. Just after she was born, I heard a screech outside and watched a barn owl fly off into the darkness. I love sitting outside on the garden wall, listening to movements in the bushes and feeding my baby under the waxing moon. I’ve never felt more mammalian.

Dark Skies by Tiffany Francis-Baker (Bloomsbury, £10.99) is available now.

Image credits: Aaron Crowe (top), Tiffany Francis-Baker (illustrations)

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.