Forget the calendar: haymaking must reconnect with the shifting seasons

Since the 1980s, the government has dictated the timing of haymaking. Climate change means these rules now benefit neither farmers nor flowers.

Lady’s-smock, yarrow, self-heal: these are some of the first plants I learned to name as a small child, my mother pointing them out in verges and meadows, telling me their stories.

My mother learned them the same way, from her mother, on the farm where she spend her childhood. My grandmother herself hadn’t grown up on a farm but developed a love for it through working as a Land Girl in World War II.

I never knew my grandmother, who passed away a year before I was born, but I always felt a connection through this shared wisdom: wildflowers forming a golden thread of family culture.

My grandmother was also a keen photographer, and I always loved delving into her old suitcase full of sepia photographs and cuttings. My favourites were those from the family farm in the 1950s, featuring jersey cows, goats, pigs – but no electricity.

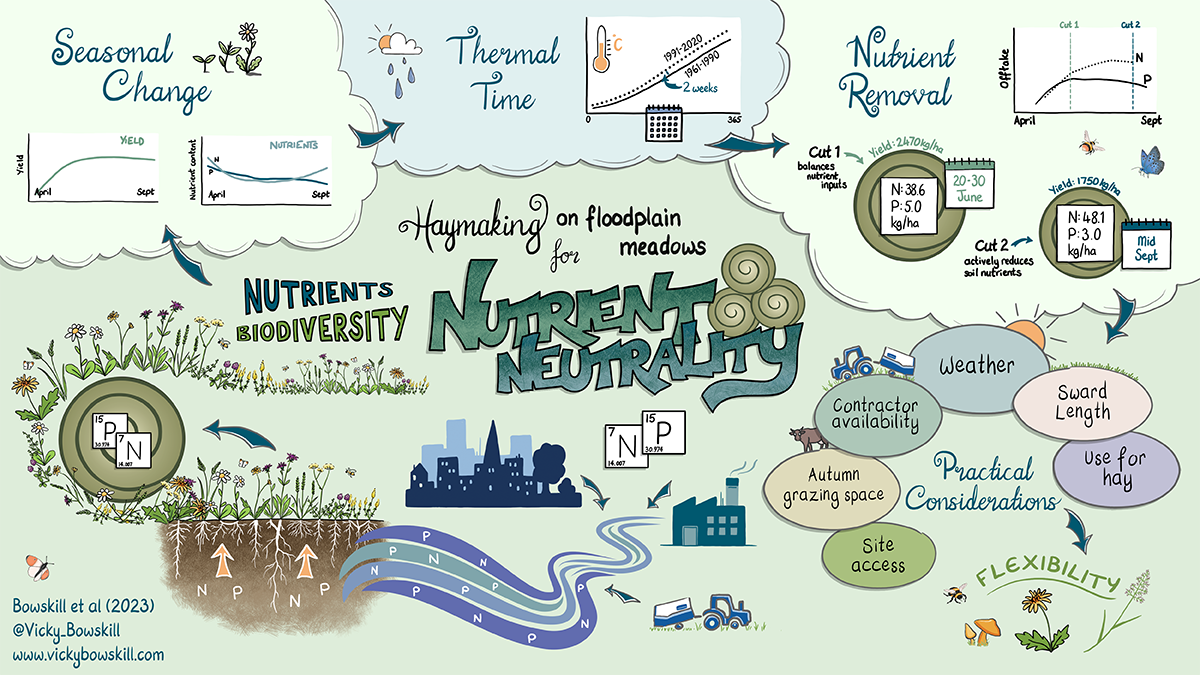

Perhaps it is little wonder that haymaking on floodplain meadows would come to be the focus of my research as an academic, some seventy years later. Specifically, I study the movement of nutrients through this habitat, and how agricultural production and biodiversity conservation can be brought back into balance through nature-friendly farming practices.

Floodplain meadows are exceptionally diverse, supporting a wealth of native plants, insects and other wildlife. In one square metre, you might find up to forty different species of plants, including great burnet, meadow foxtail and meadowsweet.

This diversity is the product of ecology, culture and time. Unlike drier meadows, floodplain meadows are regularly fertilised by the nutrient-rich sediments that are deposited on them whenever the river bursts its banks.

Left unmanaged, the meadow would be destroyed by these nutrients, which would build up over time, absorbed by the growing plants only to be returned to the soil after flowering. As a result, tall vigorous species – nettles, docks and thistles – would take over, causing many of the smaller wildflowers to be lost, along with all the life that depends on them.

Human intervention interrupts this cycle. Hay is basically preserved sunshine, cut during the summer to provide fodder for livestock throughout the winter. The plants regrow over the rest of the summer and by the autumn they provide valuable grazing for livestock – as well as late-season nectar for pollinators.

It is the cutting and removal of the nutrient-laden hay that keeps the whole system in balance, allowing so many species to thrive alongside each other while also providing an important crop for farmers.

In other words: a floodplain meadow is an excellent example of how traditional farming practices can create something more beautiful and diverse than would otherwise be there.

Before the arrival of artificial fertilisers, these naturally-fertile meadows were the fuel pump of a livestock-driven society. The Doomsday Book of 1066 records floodplain meadows as the most valuable land type, in recognition of this annual bounty.

As I crawl around the quadrats I have set out, carefully cutting and weighing samples for analysis, I cannot help but feel immersed in the history of the place.

This particular meadow, on the banks of the River Thames, dates back to the Anglo-Saxon period. Its memories are of the clomp of heavy horses pulling hay carts, the rhythmic swishing of hand scythes, and the footfall of people come to join the communal harvest, perhaps sharing a cider at the end of a long day. Though we can barely imagine it now, the rampant diversity of plant and insect life they witnessed as they drank would have surely seemed mundane at the time.

But the history of this meadow manifests in more than just memories.

Placing my palm on the prickly stubble left in the sample quadrat I’ve just cut, I think about these meadow plants – soft, tender species that are easily eaten by grazing animals. It is tempting to think of them as young, short-lived things: their leaves are cut each year, and each year they grow back.

Some of them are annual plants that grow afresh from seed each year, but most of the plants in these old meadows are long-lived perennials. Really long lived. Many of them form potentially vast clones, spreading across the meadow. Research has shown that some of these clones could be over a hundred years old – older, in other words, than even some of the trees in the hedgerows.

These deceptively small plants have witnessed the changes in how we harvest them, the decline in the number of insects that visit them, of when the floodwaters rise to nourish them, and how soon the heat builds, driving their rapid growth in the spring.

I wonder how far the plants I’m sitting on spread in their subterranean network, twined with mycelium and worms. How many summers have they seen, and how long will they stretch beyond me into the future? It is not them, but me, that is the ephemeral being in this flowing meadow.

Over the last century, floodplain hay has lost a lot of its value. Humans no longer rely on horses for transport and mineral fertilisers have boosted the fertility of land outside the floodplain.

Many of these old meadows were drained, moved into intensive agriculture or lost to development. For those that survived, changes in how the hay is harvested have also had an impact. Today, only scattered fragments of these precious meadows remain.

My grandparents’ farming days fell between two worlds. They made hay as the post-war agricultural revolution gathered pace in the 1950s, making unbaled hay by hand but hauling it by tractor rather than horse. Soon after that, however, increasingly large machinery came to dominate.

In recent decades, the meadow I am studying has been visited annually by tractors, their chunky tyres spreading the weight of the vehicle to avoid compacting the soil too deeply, dragging spinning blades that neatly slice the plants. Tines scatter the fresh leaves to dry in the sun, before gathering it into windrows for the baler to bind with twine. The whole thing takes a matter of hours, spread across a few days of sunny weather.

This process, modern as it is, has helped to preserve this meadow, against the odds, into the present day.

But climate change now poses yet another threat to these rare survivors.

Since the 1980s, agri-environment schemes have restricted haymaking until mid-July: cut earlier than this, and farmers may not receive the subsidies upon which many rely. This rule is designed to protect ground-nesting birds, keeping machines out of the fields until the young have fledged.

As temperatures rise, however, what is good for the birds has become increasingly bad for the meadows themselves. Heat builds more quickly each year, and plants are responding by growing and flowering earlier in the season as a result.

When the climate was cooler, mid-July would perhaps have been a suitable time for haymaking. Now, however, many plants will have already entered a period of summer dormancy by that point, having flowered and set seed, meaning that fewer nutrients are removed from the field when the mandated cutting time arrives.

The damage is twofold: the farmer gets less nutritious fodder for their livestock, while botanical diversity declines as nutrients accumulate in the soil and taller plants start to dominate.

Haymaking works best – for nature and people – when attuned to the flow of the changing seasons, rather than tied to an inflexible calendar. My research has shown that late-June would, on average, be a good time to harvest hay in central England – but this will vary each year, depending on weather and location: how high it is above sea level, or if it’s further up north.

With the right information, farmers can judge the timing without the need for stringent metrics, simply by observing their crops with an experienced eye, knowing their land and the species that thrive there. Post-Brexit changes to the UK’s agricultural subsidies present an opportunity to put this knowledge into practice.

Having spent a lot of time getting to know the plants in my quadrats, I feel deeply connected to this piece of land, caught in its inexorable flows of time, tradition and culture. The ghosts of the scythe-swinging folk from that scrapbook whisper of golden summers and the mellow aroma of the sweet vernal grass that lends hay its characteristic scent.

One of the gems in my grandmother’s sepia photo album is an image of two intrepid ladies, sitting in a meadow, sipping their cups of tea. With no caption, their identities are now lost to time – but I raise a flask to them now, on my own tea break, as I sit next to my sack of carefully bagged and labelled hay samples.

All images are featured here with the permission of Vicky Bowskill.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.