Cows, collars and a fake wolf: How to rewild in a very human landscape

On a Dorset peninsula, a massive effort is underway to restore the ecological processes of prehistory.

The Isle of Purbeck might seem like an innocuous backdrop to historic towns, weekend getaways and summer beaches, but this Dorset peninsula is an ecological goldmine.

Sand lizards and slow worms, nightjars and woodlarks are among the 450 rare, threatened or protected species living across Purbeck. It is a place where you can find Britain's rarest dragonfly and its fastest beetle. There are butterflies that have gone extinct across the rest of Dorset, fungi that don’t exist anywhere else in England and Wales, and wasps that you’ll struggle to find anywhere else on the planet. A 2018 report found that it harboured the most mammal diversity in Britain.

For all of these reasons, it might seem the worst imaginable place to rewild. Compared to a famous project like Knepp – which introduced grazing herbivores on an intensely farmed estate with very little environmental value – rewilding Purbeck is the equivalent of letting bulls loose (literally) in an ecological china shop.

But beneath the surface, Purbeck is facing an extinction crisis. Many of its prized species are barely hanging on in a landscape that has become fragmented: some areas have been planted over with conifers, others ploughed up for agricultural use. Back from the Brink reported that 60% of “key heathland species” are in decline.

“While we’ve stopped the loss of habitat, we haven’t actually stopped the loss of some of the really rare, threatened, specialist species which live on those habitats,” says David Brown, an ecologist with the National Trust in Dorset. Many, he says, are now "hanging on by a thread".

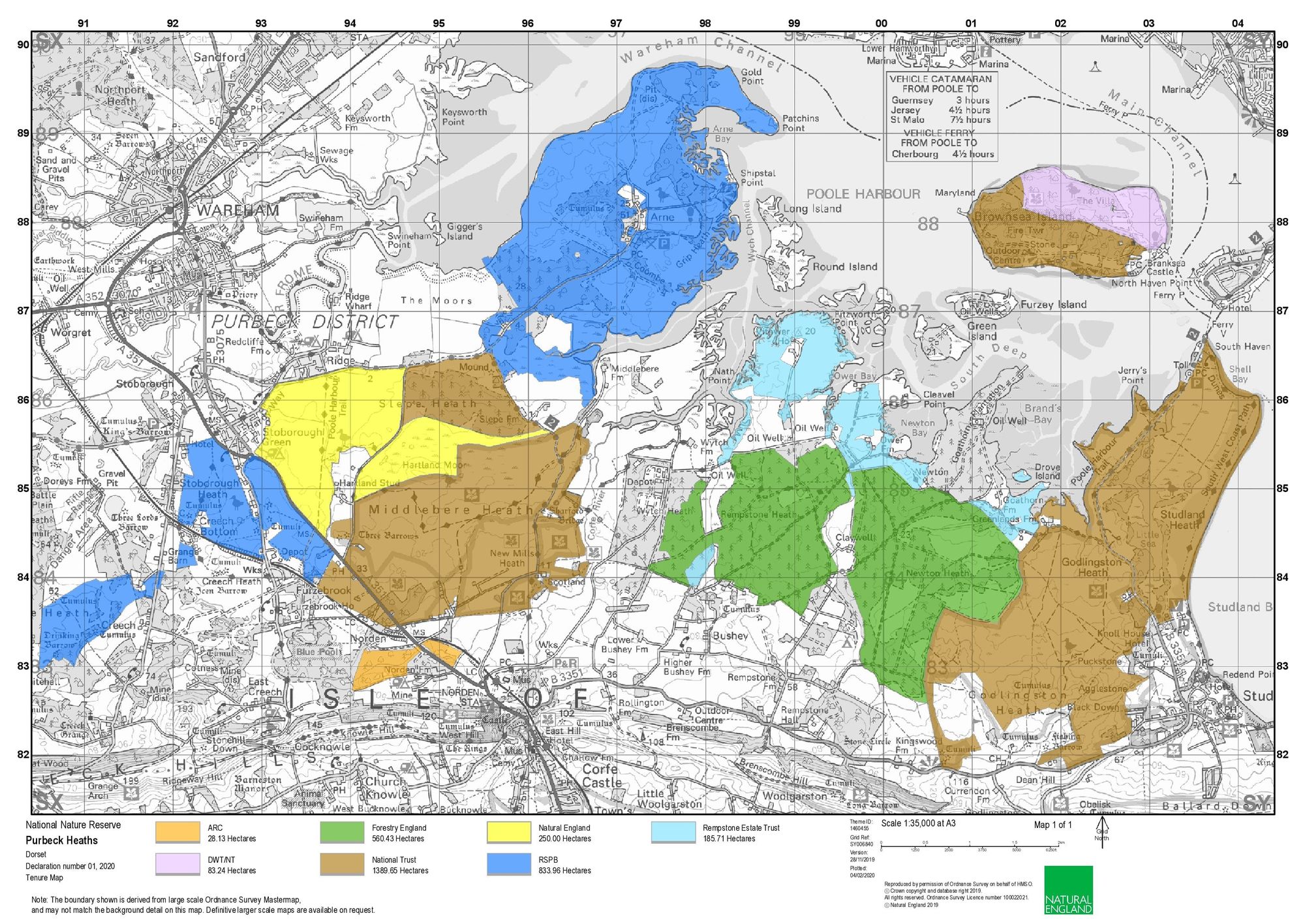

In February 2020, in an attempt to stem the decline, seven different landowners joined their plots into a connected area of 3,331 hectares: a “super reserve” the size of Blackpool, and the largest area of lowland heath managed as a single nature reserve in England. The National Trust, Natural England, Dorset Wildlife Trust, RSPB, Forestry Commission, Amphibian and Reptile Conservation and the privately-owned Rempstone Estate will continue to manage their respective areas, but now with a common vision.

Fences are coming down, and free-roaming herbivores are returning to the landscape. Soon, they’ll be directed by GPS collars which deliver an electric shock when cows wander where they shouldn’t. When equipped, wardens will be able to whip out an iPad and – in consultation with HD drone mapping and population data from the Wildlife Recorders – decide which part of the reserve needs grazing and which needs time to recover.

It’s not quite Jurassic Park level technology, but it offers a solution that fits the shifting mosaic of habitats in the reserve.

Extinction crisis

Since segments of Purbeck became protected in the 1940s, conservationists have been mandated to protect specific species or habitats, yet without a consistent vision for the ecosystem as a whole. The new reserve attempts to move away from this patchwork approach by unleashing nature on a larger scale, creating space for natural processes to unfold once again.

Yet, in a place like Purbeck, rewilding isn’t quite as simple as somehow reverting to an untouched past. Dorset has been so thoroughly altered by human intervention since the Bronze Age that it’s hard to distinguish what its "natural" state might be. Heathland, for example, only took over after prehistoric settlers cleared the wildwood, the ecological transition encouraged by the arrival of a colder and wetter climate.

The conservation overhaul now underway was inspired by the research of ecologists Andrew Byfield and David Pearman, who, back in 1994, were scathing about the traditional approach towards preserving the heathland they cherished.

"The protection of heathland blocks as nature reserves or SSSIs," they wrote, "has done little to stop the overall decline of rarer heathland plants."

Counterintuitively, Byfield and Pearman discovered that, in recent history, intensive human disturbance had acted as a lifeline to certain endemic heathland species. Everything from claypits and digging peat to slash-and-burn agriculture had inadvertently created the niches for species that thrive in disturbed habitat by mimicking the processes that would have taken place naturally – by a wandering woolly mammoth, for instance – in the distant past.

But for the past six decades, “the rapid cessation of traditional management and disturbance” brought on by protected status and “the virtual loss of grazing” had driven a “catastrophic decline”, they wrote.

To the National Trust's Brown, now chair of the science and monitoring group for the new super reserve, this project is an opportunity to restore an environment capable of supporting the flora and fauna within it without the need for human micromanagement.

He believes that relying on well-intentioned volunteers to fell pines, cut gorse and dig scrapes for sand lizards is the conservation equivalent of gardening. "The idea that we can provide all these habitat niches that nature needs with a spade is nonsense – and the idea that we can do that across a whole landscape if we want to drive nature recovery is nonsense," he says.

Guided rewilding

The new vision will reinstate the wild versions of the anthropogenic processes that would have disturbed the landscape in its heathland prehistory, including the introduction of large herbivores to graze back scrub, churn up the land and disperse seeds across the ground.

Some animals are already here. A small population of native roe deer have lived in the area and grazed pine saplings long before any reintroductions began. Exmoor ponies have been released in designated areas since 1988 and, more recently, ospreys were reintroduced to the harbour in 2017. A couple settled last summer and were joined the same autumn by sea eagles visiting from a reintroduction project on the Isle of Wight.

Now, after years of planning, 2022 looks to be a riotous year of wildness. Already, bulls gorge pits of earth to impress mates in rutting season, saving wardens the trouble of digging scrapes for sand lizards to lay their eggs. Cattle will be released into an expanded grazing area next month; beavers will hopefully join them shortly; and hulking but gentle Mangalitsa pigs arrive in May. All will graze at different vertical levels and uniquely disrupt the environment around them.

Apex predators, however, are likely to remain absent for the foreseeable future. In a completely wild environment, wolves would control the number of cattle, as well as scaring them into tight huddles. The compact herd would thoroughly disrupt one area before moving on, giving vulnerable species the time to relocate around the reserve. They would also keep non-native Sika deer numbers in check, where now they are regularly culled.

Brown used to work in Spanish uplands where wolves have been making a comeback since the 1970s and believes they would make "absolute ecological sense" in Purbeck.

In a cultural landscape like Dorset, however, it’s not so much a question of ecology but human psychology. Even in the depopulated glens of Scotland, the prospect of wolves has met with passionate resistance. In a densely inhabited landscape in southern England, the idea seems almost unthinkable. One local resident said that he “despaired at the thought”.

“Are we about to get them? No we’re not,” says Brown. “Society here is not ready to have that conversation.”

He is more optimistic about the return of the lynx. Timid, solitary and less culturally threatening than wolves, Brown hopes that the big cat could return to the heaths “within a decade or two” – or, at the very least, that the current work will lay the foundation for a future conversation.

In the meantime, the project has employed a de facto ‘wolf’, Jake Hancock. Since he came to Hartland Farm in 2009, he’s been replicating the natural effect of a predator: managing herd numbers, directing their munching and culling cows that won’t survive harsher winters without silage.

Bumps in the road

Peter Robinson runs the bird reserve at Arne, in the NNR’s northwest corner. For him, rewilding is a way of restoring something authentic about a landscape. Today, the vista “is like a colour photocopy of an old master," he says. "Grazing fills in the brush strokes.”

Rewilding has already led to some ecological surprises. Woodlarks are known to enjoy nesting in the open, unsettled areas where pine has recently been felled: not a small concern for wardens who one day hope there will be no more non-native pine to remove.

But Robinson has noticed a possible lifeline. As woodlark populations have shifted between the sites of recent felling, one group has remained consistently at the top of Arne Hill, the only area of the reserve where pigs are currently kept in the open.

Robinson thinks the pigs are somehow creating the same type of disturbance as pine felling. Once the Mangalitsa pigs arrive in May, he hopes woodlarks will be able to follow in their paths, the disruption of their hooves providing a vital habitat as pine dwindles in the coming decades.

Then there’s the Purbeck Mason Wasp, which has made its home in disrupted microhabitats like Newton Gully: a clay pit dug in 1854 and accessed by horse-drawn cart, then train, then truck, until the line mostly closed in 1937. It’s one of the very few places that this hyper-rare species can be found – partly because it is inordinately fussy. It needs upturned, slightly clayed ground to nest, and bell heather no more than two years old for nectar.

In the long run, the Purbeck Mason Wasp will benefit from ranging animals turning up more bare ground. But because numbers are already so low, it might be vulnerable to excessive disruption. Lucy, a local volunteer, claimed that a trialled grazing release had allowed cattle to trample one of their nests. A separate report found that grazing can disturb wasp eggs when they lie underground in the summer months.

Brown recognises the need for caution, but argues that it’s all part of the move away from a micromanaged landscape; focusing on individual incidents is, in the larger picture, a distraction. But until their populations stabilise at healthy levels, Brown promises that some level of “gardening” will continue to protect vulnerable species.

‘Not wild, but wilder’

For the most part, reactions have been positive. But the new reserve is not without its critics from the dog-walking community and, even after over two years of stakeholder engagement, beavers are still stirring up apprehension on local social media.

But it is the dog-walkers and invested locals that make this project so unique. Where rewilding typically conjures images of remote (usually northern) serenity, Purbeck is a lived-in landscape. One beach on the reserve’s eastern edge alone attracts 1.5 million visitors a year. It seems the very antithesis of a “wild” place.

Which means that Purbeck NNR’s presence in the midst of this humanised environment is already, inherently, a success. The project represents not so much a return to an untouched natural ideal, but a step closer to an autonomous natural ecosystem: less romantic, more practical. It’s not hands-off, zero-intervention rewilding, but it is restoring ecological processes at scale, and inviting the resultant cascades to tumble throughout the landscape. In the words of the former manager of the surrounding AONB: “Not wild, but wilder.”

If Purbeck can find its home in a broader church of rewilding, then the idea of rewilding itself no longer needs to be so divisive. And if biodiversity thrives as promised, it could become an out-and-out role model for future projects of even greater scale in the south of England.

Thank you for reading Inkcap Journal. Please consider supporting our journalism by becoming a member. Subscribers also receive our weekly digests of nature news across Britain.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.