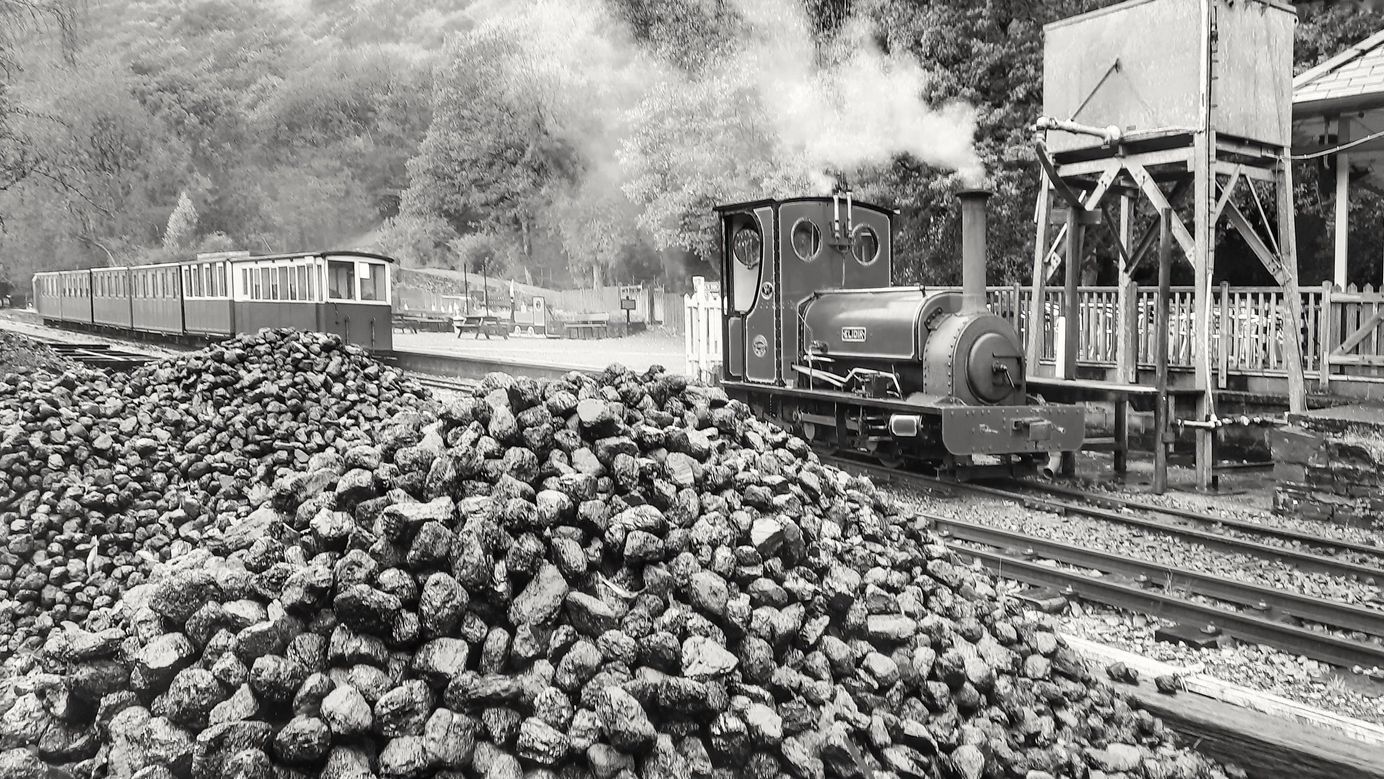

Biodiversity is flourishing on Welsh coal tips – but for how much longer?

Wales' old coal tips are havens for rare species, but their future is at risk as the government considers how to prevent future slips.

In 2016, a Welsh coal tip became an unlikely scene of excitement when a local expert found a millipede unknown to science.

Dubbed the “Maerdy Monster” after the former colliery in South Wales where it was discovered, it was believed to be the first new millipede found in the UK since 1993. The species has not been recorded anywhere else since.

But the Maerdy Monster is just one of many rare species that has chosen to make a home on these typically unloved coal tips. The sites feature nutrient-poor soils and complex topography, which has led to the formation of a rich mosaic of habitats that are hugely important for biodiversity.

A single coal tip can support a wide range of habitats, from bare ground and flower-rich grassland to heathland, wetlands, and scrub. Rare insects such as the brown-banded carder bee and the dingy skipper butterfly forage in the diverse vegetation; lizards, slow worms and newts bask on sunny slopes and seasonal ponds; and unusual fungi thrives on the undisturbed spoil.

But some biodiversity experts fear these hotspots of life may now be endangered, as the Welsh government plans to overhaul how it manages the country’s old coal tips in the interests of safety.

In February 2020, Storm Dennis brought down more than 160 millimetres of rain on the South Wales Valleys in 48 hours. The record-breaking rainfall overwhelmed the drainage system of a tip on the edge of Tylorstown, causing some 60,000 tonnes of waste – which typically consists of stone and other materials removed during mining operations – to surge down the hillside into the river below, damaging sewage and water infrastructure.

A video taken from a house opposite the landslide was widely shared on social media. The event resurrected memories of the Aberfan tragedy in 1966, when an active coal tip collapsed, releasing 110,000m3 of waste material down the hillside to engulf several houses and the village school, killing 144 people, mostly children.

Though there were no fatalities from the Tylorstown slip, the incident flagged the potential threat as rising greenhouse gases disrupt the usual weather patterns. The volume of winter rainfall is expected to increase, and storms are becoming more intense. The independent Climate Change Risk Assessment for Wales, published last year, recognised the potential for climate impacts to increase the risk of future landslides and subsidence linked to historic mining activities.

In response, the Welsh government ordered the Law Commission to review coal tip safety. In March, its report concluded that the laws and regulations governing the management of the tips, which date from the time of the Aberfan disaster, were no longer fit for purpose, given the rising impacts of climate change.

A hammer to nature

In May, the government released a white paper on coal tip management, which will eventually form the basis of a new Bill in the Senedd. The focus of the consultation was on safety – around 300 tips are considered high risk – but that leaves more than 2,000 which are considered low or no risk at all.

Ecologists are concerned that the biodiversity value of these tips could be overlooked in an attempt to secure the safety of the sites. Liam Olds, a freelance ecologist working for invertebrate campaigners Buglife, has been on what a fellow conservationist called a “one-man crusade” to raise awareness of the value of these often overlooked habitats.

Previous remediation projects have focused on tree-planting and tidiness rather than preserving the unique habitats that have naturally arisen over the years, he says, and the concern is that such mistakes could happen again.

“They are some of the richest wildlife sites in South Wales, and at a national level,” Olds says. He blames negative media coverage and rhetoric from local authorities and the government for the general blindness towards coal tip biodiversity. “Terms like ‘ugly’, ‘unsafe’, and ‘unstable’ are used, all words that make you think that we shouldn't really have these sites in our landscape.”

In its submission to the Commission, Buglife suggested that reclamation of old tips should be avoided “wherever possible” due to the impacts on species and habitats. Where remediation is essential, the organisation proposed that any landscaping efforts should consider the ecological needs of existing species.

“It is important that reclamation and remediation schemes avoid the use of fertile topsoil (as this is not conducive with a successful biodiversity reclamation), promote natural succession as much as possible, and aim to replicate the varied topographical, hydrological and chemical complexity of old coal tips that are responsible for their high biodiversity value,” according to the charity.

In addition, Buglife suggested the creation of an Ecological Stakeholder Task Force, to bring together experts from local authorities, Natural Resources Wales (NRW) and different conservation charities.

The Welsh Government was receptive to this idea, with deputy minister for climate change Lee Waters telling the Senedd in March that he would discuss the idea with climate change minister Julie James, following a question from Delyth Jewell, Plaid Cymru member of the Senedd for South Wales East, who supports the concept.

“I don't think that enough is being done to assess the biodiversity value of the sites,” Jewell told Inkcap Journal. “We need a task force that is looking at the wealth of biodiversity in these areas so that when these sites are being reclaimed, we don't lose that. Because you could take a hammer to it and say that the tips need clearing completely.”

Olds and Buglife were not alone in raising the alarm over threats to biodiversity. In consultation responses published by the Commission, one respondent suggested there should be “an environment report on every tip”, while another proposed that the potential impacts on protected species, habitats and nature reserves should be considered when deciding when to designate a site as higher risk.

While the Law Commission did not make any specific recommendations to the government regarding nature, as the topic fell outside the remit of their work, it concluded by inviting politicians to consider the “heritage and biodiversity value of the tips” in their response.

To tree or not to tree

But despite these entreaties, the government’s white paper remains thin on details concerning the preservation of biodiversity on coal tips – and contains no mention of the potential for an ecological task force. Jewell is concerned that the lack of information over which tips have been classified as high risk has led to an assumption that they should all be cleared.

A section in the report on the nature and climate emergencies acknowledges the thriving ecosystems that have sprung up on the unused tips, but only in reference to the threat posed by not taking action to make tips safer. “A tip slide would have a negative impact on Wales’ biodiversity. Improved management of tips can help reduce the likelihood of slides and as such reduce the risk of impact on existing ecosystems, habitats and wildlife,” the report says.

In a ministerial foreword, climate change minister Julie James suggested that some of the tips could be sites for tree-planting, “contributing to ecological networks and improving ecosystem resilience,” and pointing out the potential environmental benefits for local communities, which are among the most deprived in the UK.

It was a suggestion that Olds found frustrating rather than encouraging. He believes that tree-planting could do more harm than good to the open mosaic habitats on the tips.

“It is hugely disappointing to see Julie James making such a bold statement that could have serious negative connotations on Welsh biodiversity during a time of unprecedented biodiversity loss across the globe and within Wales,” he said.

Bob Vaughan, sustainable land use manager at Natural Resources Wales, which manages some coal tips on behalf of the government, also supported the re-landscaping of the “barren” tips to make them safe, suggesting they could be used for parks and woodlands – though he also believed there could be a role for natural regeneration of habitats.

The growth of vegetation, he said, could ultimately achieve the same effects as hard engineering. He added that any remediation work should consider that some tips had been designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) thanks to their unique assemblages of species.

Safety first

There are some indications that the government will consider the tips’ value for wildlife in the future, but for now the focus is firmly on safety.

In an interview with Inkcap Journal, climate minister Julie James said that the government “would be really pleased” to involve ecologists in the future, “but I think that’s probably slightly further down the line right now.”

A project at the University of Birmingham, looking into potential conflicts between tip safety and environmental legislation, is also considering the role for nature conservation, although the report has yet to be published.

Even so, remediation projects could be constrained by a lack of funding. The Welsh government has provided an initial £44 million for emergency safety work on the coal tips, but is adamant that funding for future remediation should come from the UK government, since coal mining precedes devolution.

However, the UK government has so far refused, arguing that responsibility was passed on in the devolution settlement. Plaid Cymru’s Jewell is concerned that the issue is distracting the debate around the future of the coal tips.

Ultimately, no campaigner is suggesting that the government should abandon safety concerns where a site is at risk of slipping. Equally, there is no reason to lay waste to the low-risk tips just because they are considered ugly. Over the past decades, many of these places, once considered a blight on the landscape, have transformed into beautiful havens of life.

“The coal tips,” says Olds, “are providing nature conservation during a nature crisis.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Members receive our premium weekly digest of nature news from across Britain.

Comments

Sign in or become a Inkcap Journal member to join the conversation.

Just enter your email below to get a log in link.